New professor wants to make history of physics useful for physics research

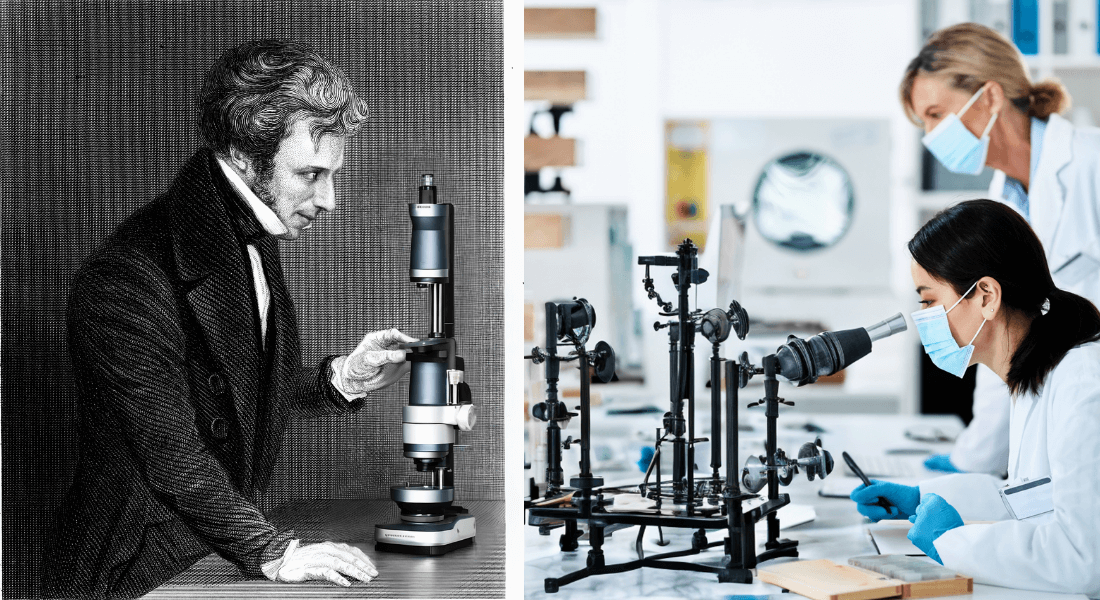

The history of physics can help physicists understand their work and their place in society, says Professor Richard Staley, who is giving his inaugural lecture on March 31st.

To research History of Science in a way that helps science. That is the ambition of Richard Staley, professor in History of Science at the Department of Science Education.

“I want to set up a project that is oriented towards the long future of physics and not just oriented towards its heritage,” Richard Staley said.

“A project that could collect material from current research projects, so that physicists working now can help collaborate in creating the archives of the future.“

Richard Staley hopes to make the connection between modern research in physics and the history of physics stronger. And being able to do research based on the archival holdings of the Niels Bohr Archive is perfect for that end.

“One of the interesting things about the Niels Bohr Archive is that it is an archive in a physics institute. Even though it is an independent institution, it is closely linked to the Niels Bohr Institute,” Richard Staley said.

A collection practice useful to science

Archives such as the Niels Bohr Archive have historically collected many materials, as individuals who have been important to physics approach the end of their lives.

"My idea is to try to create a collection practice that is useful to science as it develops," said Richard Staley, who divides his time equally between his two professorships in Cambridge and Copenhagen.

How this should be done in practice is an open question. But there is inspiration to be gleaned from other research projects, the professor points out.

"When the Human Genome Project was launched, people were aware of the potentially problematic nature of genome research and they allocated resources to research into ethical, legal, and social implications," said Richard Staley.

“And there is now a community of scientists and jurists who formed around the Human Genome Project. The aim for me here is to do something similar for physics.”

History to improve education

One possible area to focus on could be the relationship between historic archives and ongoing research in climate science, which is an element of the work at the Niels Bohr Institute.

“Everybody's aware that there's a full panoply of social implications in climate science, and maybe there's a sense amongst scientists that documenting their work is important, and that they might learn from engagement with historians, philosophers, and others. And climate scientists are building an archive of the atmospheric history of our planet too,” said Richard Staley.

Another area could be how physicists are educated.

“There is often a tension between many physicists being trained to be researchers in physics, but only a few end up in that role. Many go on to do something else. The question is, do physicists train their students to become scientists or citizens or something else?”

“So, if, for example, we collect information about education in physics and what it is like to be a PhD student, a postdoc, and a research leader in particular research fields, then you might get a picture of physics as a discipline that physicists can use to improve both the way they develop their work and help integrate physics with other fields and activities,” said Richard Staley.

Understanding place in society

If Richard Staley can find the right area and the right project, the ideal could be to persuade a research team to share the infrastructure of their working practice, helping systematise what they need to work together. To that end, historians and physicists could meet on a regular basis, and the research team could share their publications and maybe even email correspondence.

"It's the kind of insight that could be interesting," he said.

“A student of mine in Cambridge wrote her PhD dissertation on the first observation of a black hole. She made a participatory observation with the BHI group at Harvard for several months and showed how several techniques one can also trace in Art History were important for researchers developing their approach to black holes, an object that had not yet been seen.”

I want to set up a project that is oriented towards the long future of physics and not just oriented towards its heritage.

The study showed how scientists drew upon representations of black holes since the 1970s to create new physics. And in that way, the thesis provided a picture of how the new physics came into being.

"In it you can see the potential in a conversation between the two approaches," said Richard Staley.

"A collection that speaks to physics now and in the future, may help physicists understand their work and their place in society differently."